December 5, 2011

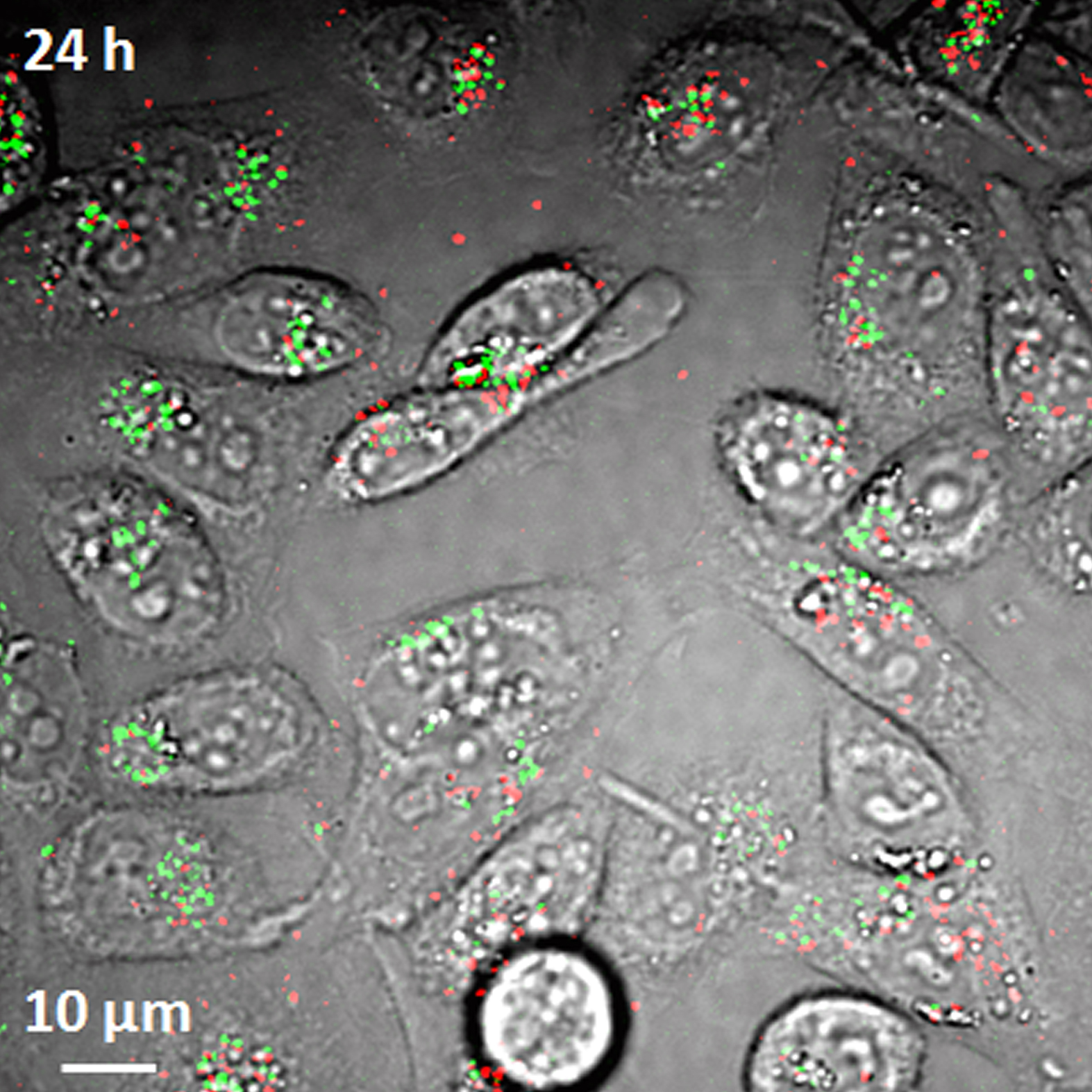

Researchers have demonstrated a new imaging tool for tracking structures called single-wall carbon nanotubes in living cells and the bloodstream, work that could aid efforts to perfect their use in laboratory or medical applications. Here, the imaging system detects both metallic and semiconducting nanotubes, false-colored in red and green, in live hamster cells. (Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University)

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Researchers have demonstrated a new imaging tool for tracking structures called carbon nanotubes in living cells and the bloodstream, which could aid efforts to perfect their use in biomedical researchand clinical medicine.

The structures have potential applications in drug delivery to treat diseases and imaging for cancer research. Two types of nanotubes are created in the manufacturing process, metallic and semiconducting. Until now, however, there has been no technique to see both types in living cells and the bloodstream, said Ji-Xin Cheng, an associate professor of biomedical engineering and chemistry at Purdue University.

The imaging technique, called transient absorption, uses a pulsing near-infrared laser to deposit energy into the nanotubes, which then are probed by a second near-infrared laser.

The researchers have overcome key obstacles in using the imaging technology, detecting and monitoring the nanotubes in live cells and laboratory mice, Cheng said.

"Because we can do this at high speed, we can see what's happening in real time as the nanotubes are circulating in the bloodstream," he said.

Findings are detailed in a research paper posted online Sunday (Dec. 4) in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

The imaging technique is "label free," meaning it does not require that the nanotubes be marked with dyes, making it potentially practical for research and medicine, Cheng said.

"It's a fundamental tool for research that will provide information for the scientific community to learn how to perfect the use of nanotubes for biomedical and clinical applications," he said.

The conventional imaging method uses luminescence, which is limited because it detects the semiconducting nanotubes but not the metallic ones.

The nanotubes have a diameter of about 1 nanometer, or roughly the length of 10 hydrogen atoms strung together, making them far too small to be seen with a conventional light microscope. One challenge in using the transient absorption imaging system for living cells was to eliminate the interference caused by the background glow of red blood cells, which is brighter than the nanotubes.

The researchers solved this problem by separating the signals from red blood cells and nanotubes in two separate "channels." Light from the red blood cells is slightly delayed compared to light emitted by the nanotubes. The two types of signals are "phase separated" by restricting them to different channels based on this delay.

Researchers used the technique to see nanotubes circulating in the blood vessels of mice earlobes.

"This is important for drug delivery because you want to know how long nanotubes remain in blood vessels after they are injected," Cheng said. "So you need to visualize them in real time circulating in the bloodstream."

The structures, called single-wall carbon nanotubes, are formed by rolling up a one-atom-thick layer of graphite called graphene. The nanotubes are inherently hydrophobic, so some of the nanotubes used in the study were coated with DNA to make them water-soluble, which is required for them to be transported in the bloodstream and into cells.

The researchers also have taken images of nanotubes in the liver and other organs to study their distribution in mice, and they are using the imaging technique to study other nanomaterials such as graphene.

The paper was written by doctoral student Ling Tong; postdoctoral research associate Yuxiang Liu; doctoral students Bridget D. Dolash and Yookyung Jung; biomedical engineering research scientist Mikhail N. Slipchenko; Donald E. Bergstrom, the Walther Professor of Medicinal Chemistry; and Cheng.

The research is funded by the National Science Foundation.

Writer: Emil Venere, 765-494-4709, venere@purdue.edu

Source: Ji-Xin Cheng, 765-494-4335, jcheng@purdue.edu

Note to Journalists: Ji-Xin Cheng is pronounced "Gee-Shin." Journalists may obtain a copy of the research paper by contacting Nature at press@nature.com or calling 212-726-9231.

Related websites:

ABSTRACT

Label-Free Imaging of Semiconducting and Metallic Carbon Nanotubes in Cells and Mice Using Transient Absorption Microscopy

Ling Tong1, Yuxiang Liu2, Bridget D. Dolash3, Yookyung Jung4, Mikhail N. Slipchenko2, Donald E. Bergstrom3,5 and Ji-Xin Cheng1,2,5*

1Department of Chemistry; 2Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering,3Department of Medical Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology; 4Department of Physics,5 Birck Nanotechnology Center, Purdue University

As interest in the potential biomedical applications of carbon nanotubes increases, there is a need for methods that can image nanotubes in live cells, tissues and animals. Although techniques such as Raman, photoacoustic and near-infrared photoluminescence imaging have been used to visualize nanotubes in biological environments, these techniques are limited because nanotubes provide only weak photoluminescence and low Raman scattering and it remains difficult to image both semiconducting and metallic nanotubes at the same time. Here, we show that transient absorption microscopy offers a label-free method to image both semiconducting and metallic single-walled carbon nanotubes in vitro and in vivo, in real time, with submicrometre resolution. By using appropriate near-infrared excitation wavelengths, we detect strong transient absorption signals with opposite phases from semiconducting and metallic nanotubes. Our method separates background signals generated by red blood cells and this allows us to follow the movement of both types of nanotubes inside cells and in the blood circulation and organs of mice without any significant damaging effects.

Fonte: Purdue University